Sphagnum moss is one of the most important and abundant groups of moss found in the Flow Country. Due to its ability to create peatlands by locking away huge amounts of carbon it plays a vital role in preventing further climate change.

The three key species of peat forming Sphagnum on the Flow Country can be seen below. However, with over 34 species present within Scotland, each has a slightly different role within the environment. A more detailed identification guide to Sphagnum mosses can be found here!

|

|

|

| Sphagnum cuspidatum | Sphagnum capillifolium | Sphagnum papillosum |

Peat formation

After the last ice age, the worlds climate changed and thus so did the vegetation. The Flow Country initially was in a warmer climate, this along with sediment left behind by the glaciers allowed pioneer species such as sedges, grasses, birch, alder and juniper to grow. Over time seeds from the British mainland arrived and forest composed of ash, elm, and alder thrived. However, the warm climate was short lived and was replaced by wetter, colder weather around 8,000 years ago. This caused the woody tree species to die out. The only remnants of their presence being tree stumps preserved within the waterlogged peat. One can be seen on the Dubh-Lochain Trail at Forsinard Flows nature reserve, find directions here!

Higher rainfall coupled with colder and damp conditions transformed the Flow Country into a very different landscape. As the wet conditions began, the forests were slowly broken down by mosses in waterlogged conditions, creating the first layers of peat.

Since the initial formations, peatland bogs have continued to expand and deepen over time. Peat continues to form when the sphagnum moss die. It doesn’t fully rot due to the acidic conditions, but instead is preserved within the waterlogged layers. These layers of moss and other vegetation are what compromises peat.

Threats

If dried, burnt or the water level lowers, Sphagnum mosses can dry out. This causes the carbon locked within the moss to be released. Therefore, the carbon that has been locked away for thousands of years is released into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas. Due to the slow growing rate of peat, it is essential for global climate change to keep the peatlands healthy so they can continue to sequester carbon over many years to come.

Current and past uses

Sphagnum moss and peat has been used for centuries for many different things such as medicines, wound dressing, in gardening, as fuel and as bedding for animals.

Sphagnum moss is most notable and well-known use is as a wound dressing. Its sponge like qualities make it suitable for absorbing blood and other fluids. Sphagnum is also an antiseptic by releasing hydrogen ions, increasing acidity and lowering the pH, the moss created inhospitable conditions for bacteria to survive. During World War 1 stocks of cotton dressings were diminishing due to the number of causalities and wounded men. At the same time a doctor re-discovered that Sphagnum was a good alternate and by the end of the war thousands of these Sphagnum dressings were being used.

The Flow County was a big exported of moss during this time, with work party’s gathered to collect in the moss, including teachers, boy scouts and prisoners of war. Read more about the uses of Sphagnum in WW1 here!

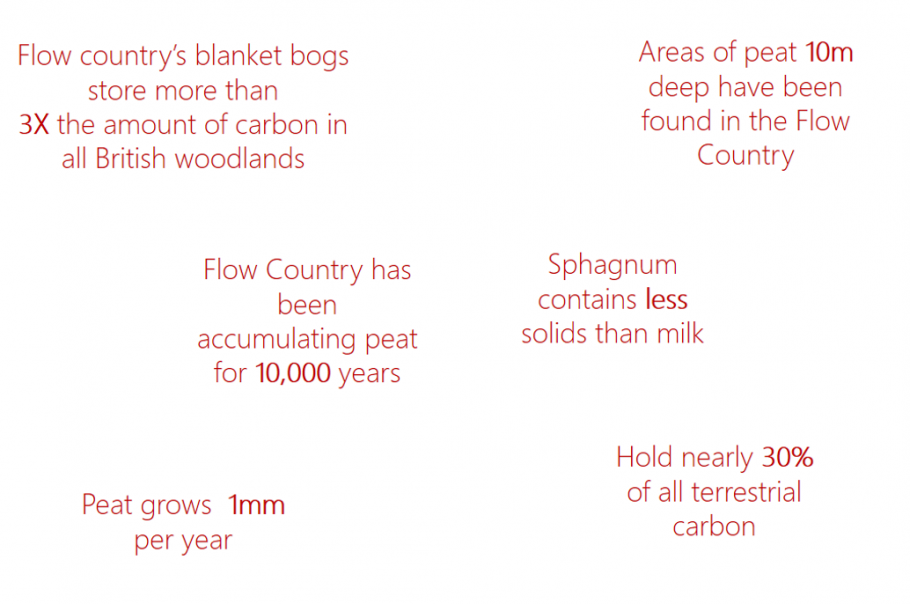

Quick Facts

Further reading

34 different species of Sphagnum in ScotlandSource: Atherton, I., Bosanquet, S., and Lawley, M. (2010). Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland – a field guide. Plymouth: Latimer Trend & Co. Ltd.

Sphagnum can hold up to 20 times its own weight in waterSource: Ayres, P. (2013). Wound dressing in World War I - The kindly Sphagnum Moss. Field Bryology, (110), pp. 27 -34

Acrotelm & CatotelmSource: Lindsay, R., Birnie, R., Clough, J. (2014). IUCN UK Committee Peatland Programme Briefing Note No. 2. IUCN Peatland Programme.

Climate ChangeSource: Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH)

Pollen macrofossilsSource: Lindsay, R., Birnie, R., Clough, J. (2014). IUCN UK Committee Peatland Programme Briefing Note No. 1. IUCN Peatland Programme.

Threats to mossSource: Lindsay, R., Birnie, R., Clough, J. (2014). IUCN UK Committee Peatland Programme Briefing Note No. 2. IUCN Peatland Programme.

Vegetative succession in Caithness and Sutherland following the ice ageSource: Auton, C., Merritt, J., and Goodenough, K. (2011). Moray and Caithness: A Landscape shaped by Geology. Scottish Natural Heritage.

Blanket bog formationSource: Lindsay (1995). Bogs: The ecology, classification and conservation of ombrotrophic mires. Scottish Natural Heritage. Source: A. V. Gallego-Sala , D. J. Charman , S. P. Harrison, G. Li, and I. C. Prentice (2015) Climate-driven expansion of blanket bogs

|